Lecture "How to Cheat at Scrolls"

The text and slides of a talk produced for use at Kingdom University 2020, which, taking place during COVID, was an on-line event.

How to cheat at scrolls

What is the SCA?

Most readers will already know the answer, so skip this section if you do. The Society for Creative Anachronism is an international organisation, originating in the USA and still having its centre of gravity there. In the absence of a better word, it is often referred to as a re-enactment group, but this is misleading. Unlike true re-enactment groups, SCA members do not, say, all dress up in late 15th century armour and re-enact the Battle of Bosworth, or as Tudor farmers to demonstrate to the public how agriculture was done in the 16th century. SCA activities are not usually done for the benefit of an audience (very few have an audience) but for the benefit of the participants. There is no requirement to dress to a particular period… each individual chooses their own garb, from the period pre-1600 (but in practice, nearly always from the mediaeval or renaissance era). So you will see Vikings and Tudors standing side by side. The emphasis, rather than re-enactment, is the acquisition of skills from the period. These include fighting skills but also the arts and sciences of the period.

I sometimes irreverently describe it to those who ask as “a cross between the Masons and the Brownies”. Masons, because we have a rather arcane hierarchy and ritual, incomprehensible to outsiders. Brownies, because the Brownies earn badges for the acquisition of skills in particular areas, and the SCA rewards skills with various awards. These awards are presented in court (a meeting of the group presided over by King and Queen or Prince and Princess) and with them should go the presentation of an award scroll. It is these award scrolls that are the subject of this paper.

What is the process for commissioning an award scroll?

Again, if you are an SCA member, you can probably skip this section. Awards are conferred by a king and queen, or by royals of a subdivision of a Kingdom (e.g., a principality) on the basis of their own judgment and of recommendations by others. Once the decision has been made to grant an award, a suitable occasion is found to present it… an occasion at which that both the recipient and the royals will be present, and there is a suitable opportunity to hold a court. As awards are usually kept secret until the moment of their being conferred, this can be tricky! The royals will then inform their Signet Clerk of their intentions, and it is the responsibility of the Signet Clerk to ensure that a scribe is found to produce a scroll in time for presentation at the event. Signet Clerk and Scribe are expected to maintain secrecy, so that the award will be a surprise. The scribe will be given the basics of what the award is for, when and where it will be presented, and sometimes further background information if known, and are expected to use their own initiative and creativity in producing a scroll that incorporates all that is needed.

This the ideal. Sometimes, there are insufficient scribes available, or insufficient advanced notice given, for this to happen. However, many people with an interest in illumination (particularly if they lack confidence in calligraphy) will produce “scroll blanks” from time to time, which they will donate to the Signet Clerk. These may include an illuminated initial letter, or a decorative border, or something else sufficiently generic that it can then be used as required by adding a written text. Provided the Signet Clerk has a bank of these and is themselves a confident calligrapher (or has access to somebody who is) these can be turned into a scroll at fairly short notice. If even this is impossible, an award may be issued without a scroll, and the Signet Clerk will be asked to ensure that a scroll is produced retrospectively (a “backlog scroll”).

This system has various implications. It means that the vast majority of scrolls are produced to a deadline, often quite a short one. Also, as they are intended to be a surprise, it is not possible to consult with the recipient about what they might like. There are two exceptions to the above: backlog scrolls and Viscounty/County/Duchy scrolls. With backlog scrolls, the recipient already knows they have the award and there is no deadline for it to be presented, so consultation is possible and time is more open-ended. Viscounties, Counties and Duchies are awarded to royals at the end of their period of service, so from the moment they win the throne (achieved by combat and lasting for a period of not less than six months depending on the role) they know they are due one. Again, this gives the scribe in question the opportunity to consult, and plenty of time to produce the scroll.

Another implication is that, whilst a Signet Clerk may have been given a whole list of awards required for a forthcoming event, the demands of secrecy mean that scrolls are not necessarily assigned to a scribe on any consistent basis. The Signet Clerk cannot say to the scribes, “Here is the list, pick the one you want to do”, as this would mean revealing more awards than is necessary. A Signet Clerk will no doubt take into account the skills of scribes, their favourite style and any known friendships between scribe and recipient where possible, but in practice the potential to do this is limited. This means a scroll is likely to be assigned to a particular scribe, or made up from a scroll blank, or even assigned to the black hole of the “backlog” list based on factors which have more to do with timing and the availability of scribes than any other factors. It is therefore not automatically the case that scrolls for higher awards will be presented with higher quality scrolls. As a scribe, the factors that will play on the work I produce will include time available, personal inspiration and motivation and my personal feelings towards the recipient at least as much as the status of the scroll. I would never intentionally produce a sub-standard scroll for anybody, whatever the status of the award. But I do now have the experience to know how to tailor a scroll to the time available. A complex scroll takes longer than a less complex one, and one that involves a lot of original design takes more time than one that is a straight copy of an original with only the text altered.

Award Scrolls in the SCA

The SCA Award Scroll has evolved into a “thing” in its own right, so much a part of SCA culture that we perhaps fail to notice what a strange creature it is!

For a start, it is not a scroll! A scroll, by definition, is a document that is stored rolled up on two spools and read by being rolled from one spool to the other. Although there is no prohibition on producing an SCA award scroll in this format, it rarely if ever happens… in fact, I have yet to see an example. In the core period on which the SCA focusses (c 600 – 1600), true scrolls were rare. The Codex had replaced the Scroll as the standard format for books. Where a document was on single sheet (e.g. legal or financial records) it was indeed common practice to roll them for storage in a pipe (hence “pipe-rolls”) but these are not true scrolls, since they are opened up and flattened for reading and not rolled from one spool to another.

Where scrolls do exist in the mediaeval period, they are often deliberately archaic. Jews continued to keep the scriptures, especially the Torah, in this format. Magicians also seem to have favoured scrolls. But in both cases, the archaism is deliberate and self-conscious, a statement that the wisdom found in them is the wisdom of the ages.

So the SCA award scroll is rarely, if ever, a scroll. In practice, very few of them are awards either, in the sense that they do not usually reflect the mediaeval practices which lie behind award documents. It was indeed custom when conferring, for example, a grant of arms, for this to be accompanied by a written document confirming the grant. Insofar as the SCA practice has a historical precedent, this surely is it. But in practice, few SCA scribes look to such grants of arms as their exemplars or inspirations when creating an award scroll.

So having said what the SCA award scroll isn’t, what is it? The answer does seem to vary somewhat from Kingdom to Kingdom. My first-hand knowledge is limited to Drachenwald, but I am a member of the various SCA Facebook groups on which “scrolls” are posted, and it would seem that approaches vary, though to what extent this is due to Kingdom culture and to what extent it is down to the individual scribes I cannot truly say. I understand that some Kingdoms do not do individual scrolls, but just produce printed examples for people to colour in. Others appear to be happy with scrolls that have no great authenticity, but just use vaguely “medieval” decoration such as Celtic knotwork. In Drachenwald, however, and clearly in some other Kingdoms, the “scroll” is often an elaborate piece of work based on a period exemplar (or exemplars) from an illuminated manuscript.

So much is this the case, that the scroll has become almost the monopoly outlet for those SCA members who enjoy period illumination or calligraphy or who have an interest in the technical side of producing inks or paints to period recipes. There is no inherent reason why this should be so… reproduction illuminated manuscripts, or original designs based on period styles could perfectly well be produced for their own value, and be entered into Arts and Science displays or competitions. Yet in practice this rarely happens. Those wishing to explore period calligraphy or illumination tend to do so through the medium of the award scroll.

There are, I suspect, two reasons why this is the case. The cultural reason… that people unconsciously imbibe the notion that this is “the way things are done” in the SCA (or at least, in their Kingdom”. And the practical reason… there is such a high demand for award scrolls in the SCA that those whose interests are in illumination or calligraphy are kept so busy that they have no time or inclination for other projects!

Since those engaged in this work are, inevitably, most drawn by the best examples of mediaeval art, the exemplars on which their work is based may be complex and beautiful works of art. They will usually not be historic grant-of-arms documents or similar. Most often, they will be religious works, since in the mediaeval period most books, and especially those on which most work was lavished, were indeed religious books. Since the subject-matter of an award scroll is itself not religious, and indeed the SCA has quite a secular ethos, reconciling these two can be a challenge!

Reasons to produce an award scroll.

• Out of a sense of duty

• The pleasure of creation

• To contribute to the life of the Society

• To develop one’s own skills as an artist

• To earn appreciation as an artist

• To earn status in the hierarchy of the society

• To express appreciation of the recipient

• To increase appreciation of the beauty of original pieces

• To learn about historic technical process (eg, ink-making)

• To learn about historic techniques of calligraphy/illumination/gilding

• To make the recipient happy

The list above is probably not exhaustive, and some of the categories would bear being broken down into sub-categories. It is intentionally in no order of importance… to ensure this, it is in fact arranged alphabetically. Probably, any SCA scribe will be driven by more than one of these motives, but few will be driven by all of them, and their priorities will vary.

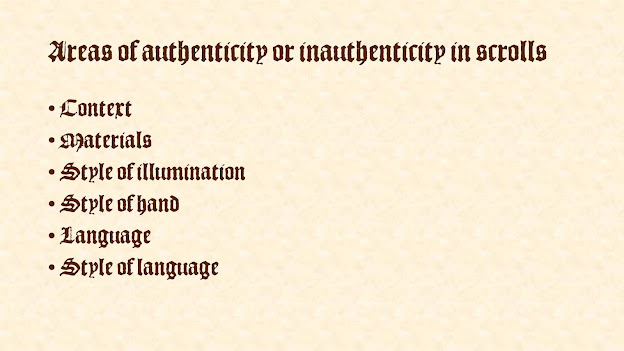

“Authenticity” is a big buzz-word in the SCA, but it will be seen that achieving authenticity does not in fact feature in all the above motives, and that various priorities of authenticity are dictated by priorities of motive.

As stated above, there is an inherent inauthenticity in most SCA scrolls. Many use pseudo-mediaeval motifs derived more from JRR Tolkien than history… viz the number of “Viking” or “Celtic” style scrolls that use knot-work or runes in ways that historically were never used on parchment. (These seem prevalent in some of the American kingdoms but are rarer in Drachenwald). But what else do you do when creating a scroll for somebody whose persona comes from a largely illiterate society? If your priority is “To make the recipient happy” or “To express appreciation of the recipient” then you may well have pitched it right.

Scrolls like this have a level of authenticity, insofar as the person producing them may well produce a piece of work that has the authentic “feel” of the exemplar manuscript, with a painting style, written hand and/or use of authentic original materials that accurately reproduces the original. But of course, they are inherently inauthentic in that one genre is being made to serve the purpose of a totally different genre.

One of the most authentic scrolls I have seen recently was that produced by Genevieve la Flechier for Edith of Hedingham. Outside the SCA, Edith is a guide for the City of London, and so she modelled her Laurel ceremony on that introducing a new member to a guild, and requested a scroll based on the scroll that would have been used at such an event. The piece Genevieve produced was skilfully executed, and had the inherent beauty that good calligraphy can bestow. But it was, dare I say it, not pretty. It couldn't be pretty… the original on which it was based wasn't pretty. True historical award scrolls were fairly dull, certainly compared to the best of the Psalters, Books of Hours and the like. If the award scroll is to be the medium by which the artists of the SCA express themselves (and as stated above, for quite understandable reasons this tends to be the case), authenticity will work against ambition and variety.

Another issue around authenticity is originality. The most authentic scrolls will, by definition, be those which most slavishly copy an original piece. Many of my own works are just this, with such minimal changes are necessary to personalise it to the recipient and serve the purpose of being an award scroll. It is the best way to do it if your motive is “to increase appreciation of the beauty of original pieces”, and I know that I can reproduce even quite a complex piece relatively quickly if all I need to do is copy… important when a work has a tight deadline. It is a quick way to produce something that looks good and will delight the recipient.

To copy or not to copy?

Any given artwork could only be viewed by a limited number of people, and if it was good, it was worth exposing to a wider audience. Many clear examples exist of two manuscripts (or details of manuscripts) whose illuminations are so clearly similar that one must be a copy of another, or both must be based on the same lost original. A visitor to a library might make a sketch of an illumination that he admired and use it later, or even ask to borrow the book to copy it (copying would also have applied to the text, in the days before print). We know that Pattern Books existed with some examples of decoration that illuminators could draw upon.

What did not really exist was an easy method of mechanically copying from one book to another. There is clear evidence that the notion of holding parchment up to a translucent surface so as to trace from it was known at least as far back as the Lindisfarne Gospels (effectively, what we would now use a light box for) but of course this was not practical to do when copying a bound codex. So whilst it easy to find examples where something is clearly derived from an existing predecessor, it is also clear that the copy was done free-hand, and thus was not an exact copy… and indeed, the copyist might well make some deliberate alterations in the process. A well-known example is the way the calendar paintings from the Grimani Breviary are clearly closely based on the Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. But where some are very close based on the older book, others relate to it much more loosely… and none are identical.

Copying historic artefacts is part of the ethos of the SCA, and in other artistic disciplines, the accurate replication of, say, a garment or a bag from our period is something for which credit will be given in Arts and Sciences competitions. Copying a page of a mediaeval illuminated manuscript is good SCA practice, and the outcome of necessity is authentic. Yet producing an original piece of work which has a convincing “mediaeval” feel to it has another type of authenticity, for this was the authentic working method of the scribes of the age… they worked within conventions and prevailing styles, they sometimes copied directly, but there were always fresh elements that they brought in.

But when I have time and inspiration, I like to either start from an original piece and vary it considerably, or even create a wholly new piece “in the style of…”. An example was the Laurel Scroll I produced for Victoria Pieri Roselli, which was a double-page spread based on Birago’s “Sforza Hours”. The first page was an almost exact copy traced from of a page from the book (except that I felt he hadn’t done his peacocks very well, and I could do better, whilst still looking “period” and I incorporated her arms and changed the text). The second page was almost entirely my own creation. Some of the decoration down the sides was copied freehand from Birago but otherwise it was all my invention… yet using motifs that are found in the Sforza Hours such as putti, portraits in circles and paintings of animals in landscapes, and attempting to use a similar style. The two pages have their own authenticities… the slavish copy is authentic in that it looks like the original, but the other is authentic in that Birago himself, though using a limited number of motifs, played with them endlessly to produce a new design for each page of the Sforza hours. I therefore authentically produced his modus operandi, but not his work.

The fact that I “improved” Birago’s peacocks raises another question about authenticity. I felt justified in doing so because even if Birago himself wasn’t very good at peacocks, other artists of his day were, and Birago produced some other very fine animal paintings in the Sforza hours. There will always be a tension in SCA work between producing a reproduction of an original period work or style, and producing an original piece of art. The SCA scroll-maker is, in the end, not attempting to produce a forgery… the end result is his or her piece of work. We need, perhaps, to be liberated by those words “creative anachronism” in our Society’s title.

My own priority in producing a scroll is the visual impact. Yet here again is an inauthenticity… or a potential one. I confess that the wording I use in my scrolls is primarily dictated by what space is left for it once I have decided what Illumination I want to include and therefore what space it has to fit in! But of course, the illuminator on which I am basing my work did not have such freedom. The Bible is a sacred text… if you are producing an illumination, you do not alter what the Bible says because it doesn’t happen to fit the left-over space in your scroll! Even if you are producing a genuine grant of arms document, it is not the scribe but the King or other bestower and the conventions of the day which dictate the wording. There were tricks of the trade… mediaeval documents made considerable use of conventionalised abbreviations, and there can be little doubt that the choice of whether to use an abbreviation or write a word out in full was often dictated by the need to fit wording into a particular space. We cannot know for certain how much give-and-take and discussion there was between scribe and illuminator… probably they were sometimes, like me, the same person, but often they were not. Unfinished manuscripts often show the basic design drawn in, so that the scribe knew what space he had to work around, but painting came after the text was written.

Text itself, of course, has its authenticity and inauthenticity. A few of our scribes (Ari Mala springs to mind) lay great stress on producing authentic-sounding wording, often written in archaic English or Latin as would be the case for the original. This linguistic study is itself as much a part of the “authenticity” of a scroll as the painting and calligraphy. But again, there is a tension. To my mind, a scroll is there to serve a purpose, and a scroll which is incomprehensible to a reader does not serve that purpose. My texts are all in English (except a couple I have done for people whose first language is something else, when I have used English alongside their native tongue). As I am very familiar with the Book of Common Prayer, I can generally produce a form of English which has a slightly archaic feel whilst still being comprehensible to a modern reader… but generally, the language used in the exemplar piece is Latin, and I have no expertise in the language used in historic grants of arms. I make no pretence that my texts are “authentic”, merely that they serve a purpose.

These five letters are not used in the classical Latin alphabet. Here is how two faux-mediaeval fonts have chosen to tackle them... note that the one in the middle has done as Latin would, and rendered "j" as "i" and "v" as "u", whilst that on the right has distinct letters for "j" and "u".

Authenticity of materials is also important to many SCA scribes, though few scrolls are fully “authentic” in this regard. Rather, there is an accepted culture of what materials may be used. The original material on which most exemplars were written was parchment or vellum. This is hard to obtain and very expensive nowadays, and being the skin of animal, can cause problems with vegan recipients. Most SCA scribes use pergamenata, a modern plant-based alternative which visually resembles parchment in its finish and translucency, and reacts to ink and paint in a similar way (they sit on its surface, rather than soaking in as with paper). Modern gouache paint is similar, though probably not identical, to a type of paint used towards the end of the SCA period and is therefore reasonably authentic, at least for later period scrolls. A number of SCA members are adept at making ink to historic recipes (usually based on ink-gall)… I use this if somebody cares to give me some, but frankly, would rather use my time making a scroll than making the ingredients, and tend to use modern inks. Metal nibs are widely used by SCA scribes, but were rare in period… those who use quills are more authentic, and the difference does show. However, I have not yet learned to make a usable quill.

Many scrolls use gold. Historically, there were two types: leaf gold and shell gold. The first was very thin gold glued to the page… it gives a vivid shine. Modern metallic paints really do not replicate it, but are nevertheless sometimes used, for reasons of cost or the confidence of the scribe. Modern gold can come on a backing paper (transfer gold) which is much easier to use and gives the same end result but is not a period technique. Modern acrylic-based materials can be used as the size (glue) to stick it down, but many SCA scribes are adept at mixing more historically authentic materials… the end result is visually much the same. Shell gold was powdered gold in a medium, which is effectively what modern gold paints are (though they use cheaper metals of similar colour). As such, modern paint is a reasonable substitute for shell gold where it is not for leaf gold.

Is authenticity about the material or the final effect?

Having looked a the theory of cheating in scrolls, the next part of my talk is more practical, looking at some modern materials and tools that were not available to period scribes and illuminators, but which are available and useful for us.

Some cheats!

There are many SCA classes that will show you how to do things in a proper period way. This is where I give away some of my tricks of the trade that use resources that were not available to period scribes, but which they would have loved if they had existed!

Computer. Computers, of course, impact almost every facet of modern life, and they certainly have their uses in producing scrolls. I use mine in the following ways:

• Research. Although I have a fairly extensive library of books about illuminated manuscripts, including a good few facsimiles, they inevitably give access to only a fraction of the number of original manuscripts that exist out there in www-land. Increasingly, libraries and museums which house historic manuscripts are making them available digitally. Such digitalised manuscripts are depressingly hard to track down on a google search, but they are there. Google does rather like to give you Pinterest shots of mediaeval manuscripts, which unfortunately usually lack context, though they can be helpful in giving some initial ideas.

• Printing. Printing out an image of an original manuscript onto standard paper (80gsm or thinner) gives you a good translucent image, which can be placed under pergamenata on a light box for easy tracing. So even if you have a book with an image you want to use as your source, it is worth scanning it or finding an on-line equivalent so that you can re-print it on paper.

• Text layout. Spacing text around an image must have been a major undertaking for the original scribes, involving a lot of trial and error. It is much quicker and easier to do it on the computer, using a font that is roughly equivalent (at least in how it spaces letters) to the hand you intend to use. Some widely-available modern fonts derive from period hands (eg Old English from Gothic Quadrata, Book Antiqua from Humanist hands), and It is quite easy to add new fonts to your computer: just google and a lot of free download ones will come up, many of them based on historic hands. Always be aware, however, though it is best not to allow their forms to dictate to you too much… they are not exact equivalents and though they are a useful guide to spacing and help you to head off any spelling errors, they should not be copied exactly. Particularly watch out for the letter “s” which in most historic hands appears in two forms… when I am using a computer to lay out text, I substitute an “f” where appropriate.

• Layout of pictures. If I am combining various elements into a design, it is much easier to do on the computer than with frequent re-drawings. Even if the design is my own, I tend to scan my own drawings so that they can easily be resized or re-positions. For all this I use Adobe Photoshop.

• Keeping a record. As the finished scroll will be presented to somebody else and I will probably never see it again, it is best to scan or photograph it before it goes so I have a record of my work.

How much is this a cheat? Using a computer saves a massive amount of time. Research could take ages poring through various books in libraries. Printing out an image for tracing on a lightbox saves drawing free-hand or tracing with tracing paper. Using a computer to do layout saves the repeated sketching and re-drawing that is necessary otherwise. So computers take out a lot of the preliminary work that mediaeval scribes would have had to do. But the finished work still has to be done by hand, and still requires manual skills… the computer helps, but does not do the job for you. The saving of time is crucial, given the short deadlines that scribes are often working to and the high volume of demand to which they are often subjected.

Light Box. A Lightbox is a very good tool for transferring a preliminary design onto the final piece of parchment or pergamenata, whether tracing from a computer-printout of an original design or from one’s own sketches. Provided the original is on something fairly translucent (thinnish paper, perhaps), the pergamenata, which is itself translucent, can be placed over the top, both layers taped down and the design traced through with a hard pencil.

How much is this a cheat? Less than you might imagine! According to Janet Backhouse and Michelle Brown, “the artist-scribe was a gifted calligrapher and a technical innovater, who seems to have invented the lead pencil and the equivalent of the lightbox to enable him to devise such an elaborate new layout”. Brown, The Lindisfarne Gospels, British Library. The artist-scribe in question is the one behind the Lindisfarne Gospels (early 8th century!). Admittedly, his probably didn't plug into the mains.

Yellow Frog Tape. This is sold in hardware shops (B&Q stock it) as a masking tape. It peels far more easily than standard masking tape even after being in place for a long periods, and will come away from Pergamenata completely cleanly (not so from paper, though you shouldn’t be using paper for the fair copy anyway). Frog tape comes in yellow and green, but the yellow is definitely best for our purposes. It is the ideal way to hold down a piece of pergamenata or parchment to a board or light-box. If you doubt your ability to paint a straight line, you can also use it as masking tape as intended, though the end result will look mechanical and give a raised edge which you don’t really want. And it can also be used, a bit like an eraser, to lift pencil marks.

How much is this a cheat? Totally, I imagine! I don’t know how period scribes held their sheets in place, One imagines that they must have used something. If it was pinned or glued, it may well be that the edge had to be cut away afterwards. That said, there is little evidence in period depictions of scribes to suggest that the sheet of parchment was fixed in place.

OHP acetate. Hard to get hold of nowadays, as OHPs have been supplanted by digital projectors, but any sheet of clear plastic will do. I use it sometimes, with a bit of Yellow Frog tape to secure it, to protect the finished part of a scroll whilst I am working on another part, keeping my hands or any splashes of paint, ink or water from damaging completed work.

How much is this a cheat? The period way to keep hands from smudging or depositing grease on the page was to rest them on a long stick held just away from the sheet.

Pergamenata. This is designed to be a good substitute for parchment, thus keeping down costs. It is also vegan-friendly! It attempts to mirror the appearance of parchment both in colour and translucency. Also important from our perspective is the way ink and paint interact with it. They sit on the surface as with parchment, rather than soaking into it as with most papers. One advantage of this is that errors can usually be corrected by scraping the mistake off with a craft-knife… though once you have done this, the surface is compromised and re-applications of ink or paint will soak in. It is very vulnerable to damp, however.

How much is this a cheat? It is a modern material, and not a wholly convincing substitute for the parchment that was used in period. But it is more affordable, and vastly superior to using paper. Paper was available towards the end of the SCA period, and used for printed books, but not for manuscripts. Paper responds very to ink and paint differently from parchment. If you are not going to use parchment, use pergamenata.

Acrylic Gold size. This is the “glue” that sticks gold leaf to the page in modern gilding. It works well, once you get the hang of it… I find you need at least two, preferably three, layers before applying the gold. Alternatives can be made using more period materials such as gum Arabic, sugar and honey. They are just as easy (or hard!) to use, but I have never got the hang of making them properly myself. Both are used in the same way (applied, left to dry and then reactivated by breathing on them).

How much is this a cheat? It is a modern material, but the techniques for using it are identical to those for the period materials. In terms of the final effect, there is no difference, since the size is invisible under the gold.

How much is this a cheat? Period scribes had no equivalent, and had to learn to handle the loose leaf, which is quite an art. The end result, however, is identical.

Gold paint. Gold paint can be used as a cheaper alternative to real gold, but in the case of gold leaf, it is a very poor substitute. In the case of shell gold, it is not so bad… shell gold was gold powder in a medium, and that essentially is what gold paint is, though it rarely uses real gold. Shell gold had a grainer, less shiny finish than leaf gold, and so does gold paint.

How much is this a cheat? If used as a substitute for gold leaf, it will result in a finished piece that looks obviously different from the original and lack the “wow” factor of real gold. But finance or inexperience with gilding may make it necessary, and gold paint is better than nothing. A good gold paint will look quite convincing as an alternative to shell gold.

Conclusion: All SCA scribes cheat at scrolls, some more than others. Wholly avoiding cheating is not possible (eg, some mediaeval pigments were so poisonous they are not now available) or hideously expensive. There is also a certain amount of "cheat" that is inherently built into the process: any scroll that uses as its exemplar anything other than a "Grant of Arms" or similar is a misapplication of the original purpose of the exemplar. And of course, the whole honours system which exists in the SCA and which Award Scrolls mark, though it has some parallels with mediaeval practice, is a modern construct. But that's all right. Creative Anachronism is what we do.

When planning an award scroll, therefore, be realistic with what you intend to achieve. What is your main purpose in undertaking the exercise? What do you want to get out of it? What specific skills do you want to develop? In what way will doing this scroll best assist you in the SCA aims of learning more about our period by doing, and of chivalry (for surely, producing a work of art to honour somebody else's achievements is a chivalrous act).

Glossary:

Codex (pl. Codices): A series of pages bound together at a spine. In general usage, we tend to use the word “book” to mean the same thing, but a book can be in any format… before codices, there were scrolls, in our own age, the Kindle e-book is supplanting the codex, yet all are books.

Exemplar: A historic object (here, a text and/or illumination) on which an SCA scribe bases their work, either as a direct copy or as a guide to style.

Gouache. An opaque water-based paint.

Illumination. Decoration on a written piece of work. Typically, this may be decorated borders, pictures or elaborate decorated letters. Usually painted rather than drawn in ink, but there are exceptions. Illumination often incorporates the use of gold (leaf or powdered in a medium) and strictly speaking, the gold is what gives the term its meaning… the flashes of light reflected from that gold are what “illuminate” the text.

Papyrus: A writing material made from an Egyptian water-reed. The principle writing material of the ancient and classical world in the west. It was supplanted by parchment in the early Christian era, and this coincided with the change from scroll to codex as the main format for books… probably not by chance.

Parchment: A writing material made from animal skin, particularly that of sheep or goats. The name derives ultimately from the city of Pergamon, where it was first produced as an alternative to papyrus.

Pergamenata: A modern writing material designed to mimic parchment: like the original Latin word for parchment, it harks back to the origins of parchment use in Pergamon.

Roll: See Scroll

Scribe: Historically, one who writes out a text (not usually of their own composition). In the SCA, the term is often used loosely of anybody who produces a “scroll”, whether they write or illuminate.

Scroll: Historically, a long piece of rolled-up writing material (e.g. papyrus, parchment, paper or cloth) on which a text is written, usually intended to be read by unrolling the paper at one end and rolling it up at the other so as to move the text along. Sometimes with batons attached to assist the rolling and unrolling process. Modern English and my usage here distinguish it from a roll, which is writing material rolled up for storage, but read when fully unrolled (so usually shorter than a scroll). This distinction is not always found in older usage. Within the SCA, the term “scroll” is used as a catch-all term for any document presented with an award, irrespective of style or material.

Size: Can mean a material used to prime a surface for painting, but in the context of manuscript illumination, more likely to mean a glue used to hold gold leaf in place. In this context, it is designed to dry in place and then be re-activated by the moisture from breath just prior to applying the gold.

Vellum: A writing material made from animal skin, particularly that of calves.

Comments

Post a Comment